The Idea Guy Learned to Ship

How agent orchestration and a filmmaker's instincts turned a boring prototype into a full-stack RPG in 5 days.

I've been vibe coding since before people called it that. For most of that time, I was the idea guy. I'd show up to hackathons around the world with a pitch, a vision, and zero ability to build the thing myself. ETH Global in Thailand. Sozu Haus at ETH Denver. I'd find programmers, sell them on the concept, and present the final product on stage. I was good at that role. But I was always dependent on someone else to turn my ideas into something real.

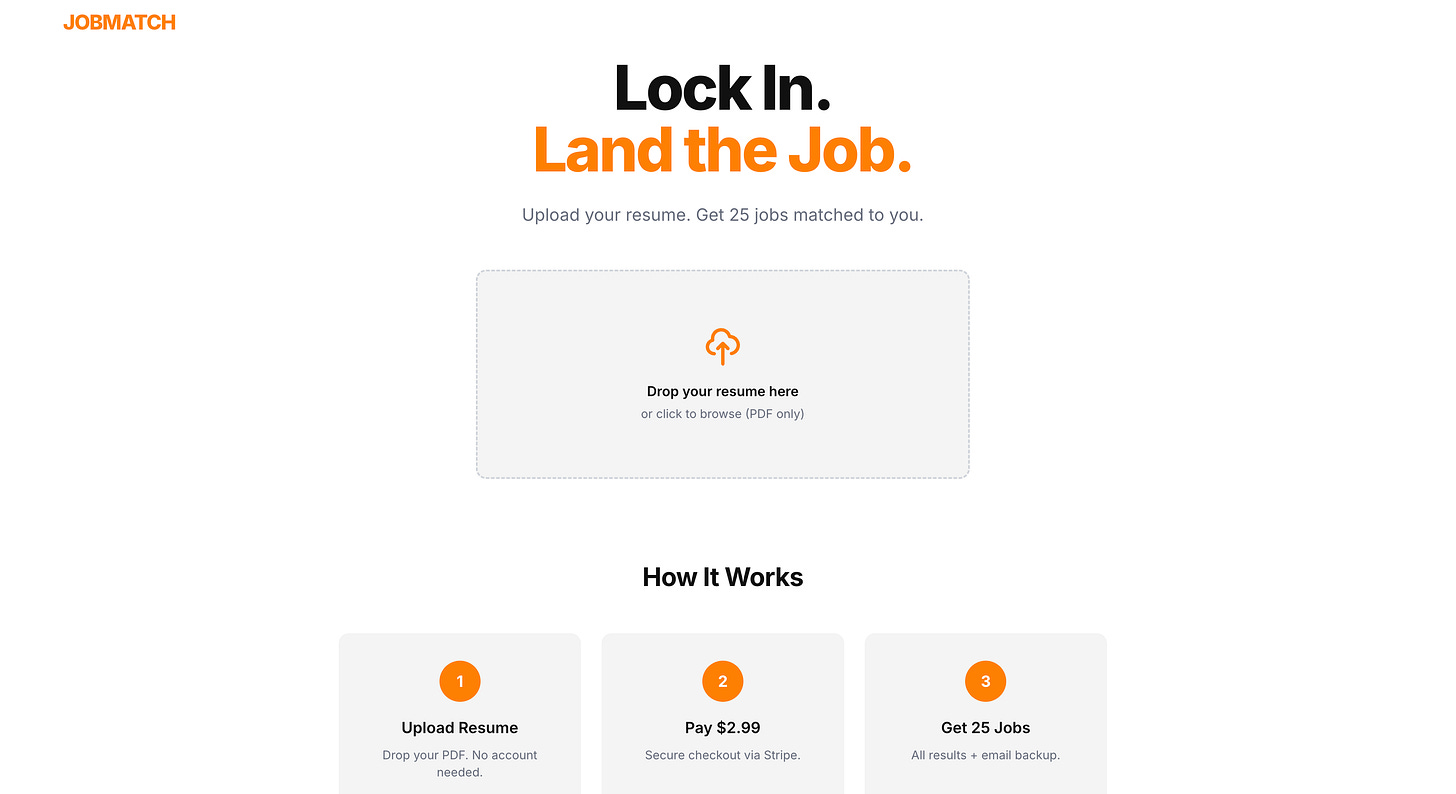

Opus 4.5 changed that. Late December, I built JobMatch, a job matching service that parses resumes and serves curated listings. It’s live at Getajob2026.com. Not a localhost demo. Not a proof of concept. A product, on a domain, that people use.

That was the moment it clicked. In the process of building JobMatch, I learned more about development and code architecture than I ever picked up from YouTube tutorials or documentation rabbit holes. Working with a model that could explain its reasoning while building alongside me was better than any bootcamp. By January I was deep into Jianghu, a wuxia narrative RPG based on Jin Yong’s Legend of the Condor Heroes. I went from idea guy to builder in about six weeks.

But V2 of Jianghu, the version I had by early February, was honest-to-god boring. 85% of player inputs were click-to-advance. Combat was one button. Decision density was one meaningful choice every 60 to 180 seconds when it should have been one every 15 to 30. It was an interactive novel pretending to be a game. I knew it. I just hadn’t figured out what V3 should look like yet.

Then Opus 4.6 and Codex 5.3 dropped on the same day.

The System That Made the Swap Possible

I need to explain the architecture before I can explain what happened, because the architecture is the whole point.

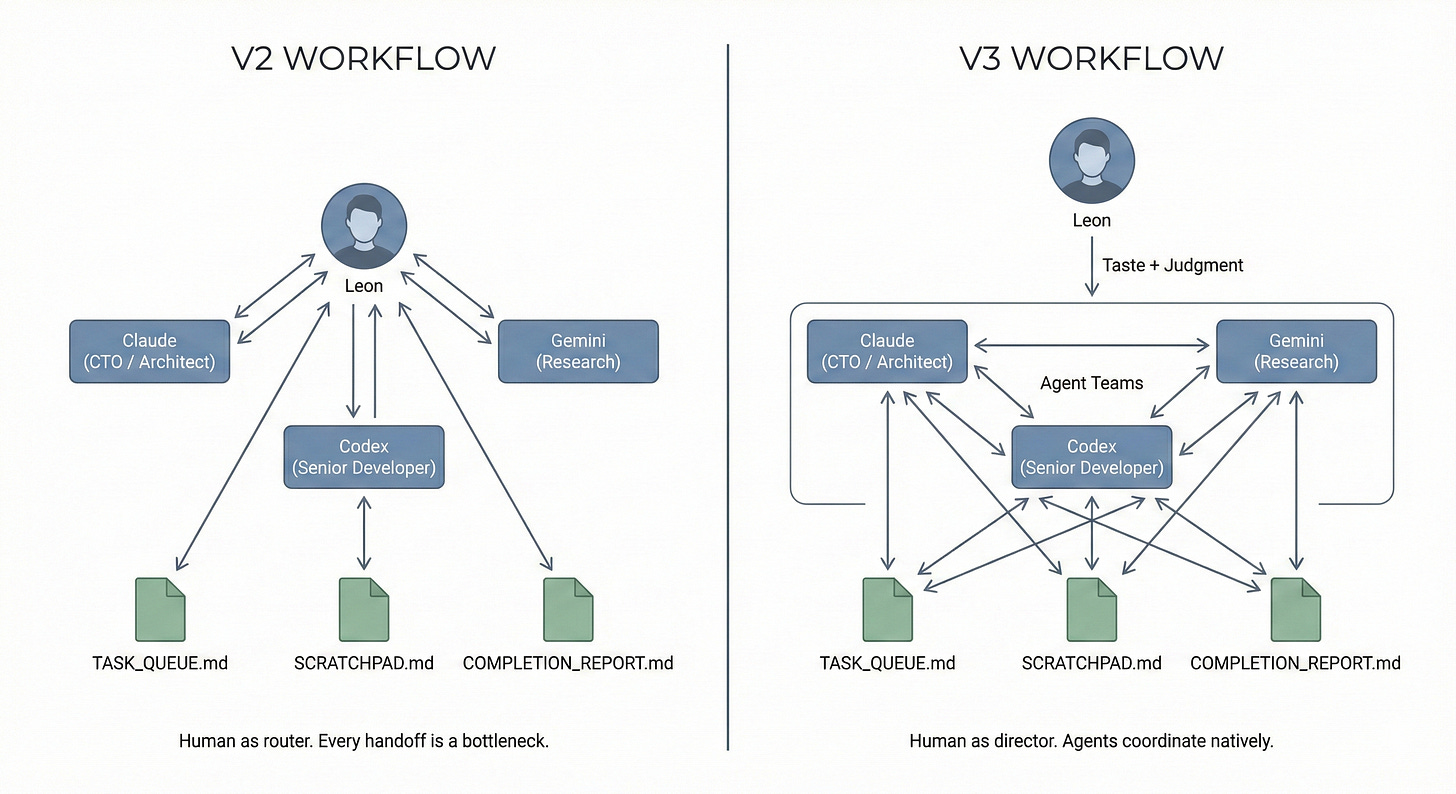

For V2, I’d built a multi-agent development workflow. Claude as CTO and architect. Codex as the senior developer handling implementation. Gemini for research. They didn’t communicate through some custom orchestration platform. They communicated through three markdown files: TASK_QUEUE.md (what needs doing), SCRATCHPAD.md (working memory and decisions), and COMPLETION_REPORT.md (what got done and how it deviated from the plan).

The whole system was designed around one principle: preserve context across sessions so agents always have the latest state and don’t hallucinate. Every decision, every deviation, every open question gets written down. When a new session starts, the agent reads the files and picks up exactly where the last one left off. No context rot. No repeated conversations. No “wait, didn’t we already decide this?” loops.

Because the communication layer was markdown, it was model-agnostic by default. The agents didn’t care which model was reading and writing. They cared about the protocol.

So when Opus 4.6 arrived with agent teams and a million-token context window, and Codex 5.3 showed up with dramatically better agentic performance, I didn’t redesign anything. I swapped in the new models like a director recasting roles with stronger actors. Same script. Same blocking. Better performances.

One evening with the upgraded cast produced a full technical audit of V2, a brutally honest player review (three AI agents actually played through the game and tore it apart), and a complete V3 development plan with six milestones. Four specialist agents ran in parallel: gameplay architect, tech architect, narrative designer, market researcher.

That evening would have been four to six weeks of solo work without AI.

When the Machine Starts Having Taste

Here’s something nobody warned me about.

Previous models could follow instructions well. They could generate plausible output for almost any request. Opus 4.6 was different. It made design decisions I actually respected.

The V3 plan included a daily Qi dice pool inspired by Citizen Sleeper that solved V2’s entire engagement problem in one mechanic. Where V2 had players clicking through text, V3 would hand them 3 to 6 dice every morning and ask: where do you spend these? Training? Exploring? Building relationships? Suddenly every day started with real decisions and real tradeoffs.

It proposed shifting scene authoring from TypeScript to JSON validated by Zod schemas. Not a flashy suggestion. But it meant that later, when we needed to author 27 branching narrative scenes, none of them required touching actual code. That’s not just a technical call. That’s someone thinking two milestones ahead about how content creation should flow.

The model restructured a 1,434-line monolithic state store into six focused modules before writing a single game feature, because it recognized that the technical debt would compound with every system built on top of it. It designed the combat system with stance-based mechanics (pressing, holding, yielding) that created emergent strategy instead of the “press attack and watch” loop from V2.

These aren’t instructions being followed. This is judgment. And the gap between an AI that executes your taste and an AI that contributes its own is enormous. It’s the difference between a session musician playing your arrangement and a collaborator walking in with ideas that make the song better.

The Tastemaker's Advantage

Rick Rubin doesn’t play instruments on most of the records he produces. He’s not in the booth laying down tracks. What he does is listen, make calls about what serves the work and what doesn’t, and push artists past what they think is possible. Nobody questions whether he’s a real producer.

That’s closer to what programming looks like now than anything I learned watching coding tutorials.

A year ago, if I wanted to build a combat system with stance mechanics and momentum, I’d need to either learn game development from scratch or convince an experienced programmer that it was worth building. And experienced programmers have strong opinions about what’s practical. They’d scope it down. They’d tell me what’s realistic for the timeline. They’d build what they knew how to build.

I don’t have that baggage. I don’t know what’s supposed to be hard, so I just describe what I want and push the model until it gets there. When Codex improvised combat values during Milestone 2 because my brief referenced a design spec by section number instead of including the actual tables, I caught it. Not because I could read the code and spot the bug. Because the game didn’t feel right. The numbers were off. I pulled Claude into a debugging session and we traced it together.

Then I established a rule for every brief going forward: include exact numeric tables inline, never reference external specs by pointer. That one process fix eliminated an entire class of errors for the rest of the project.

This is what the work looks like now. I cut sound effects and kept only background music because atmosphere per dev hour mattered more than feature completeness. I killed mobile optimization because the demo audience would be on laptops. I decided a wuxia cultural mechanic should be a dialogue choice, not a standalone subsystem. I pulled the hackathon submission writeup from the AI’s task list because that document was too important to delegate.

The future of work isn’t “everyone learns to code.” It’s that the people who know what should exist, and have the taste to know when it’s right, can finally build it themselves. The creative bottleneck was never ideas. It was execution. That wall is gone.

The Numbers

The V3 development plan estimated 22 to 29 days across six milestones. We shipped in five. Each milestone came in at 4 to 5x faster than estimated, with the acceleration compounding as the workflow tightened.

What actually shipped: a daily Qi dice pool with resource allocation, stance-based combat with momentum and technique affinity, eight explorable locations with NPC schedules, a verbal duel engine with skill checks, 27 authored scenes across seven in-game days branching into five distinct endings, and 171 automated tests with zero lint errors.

A year ago this would have taken five to seven months. And I wouldn’t have been the one building it.

Ship the Script

Film school teaches you something that engineering culture often resists: the script is never finished. You write a draft, you put it in front of people, and they catch things from angles you never considered. You can perfect your vision in isolation for months, or you can get feedback that reshapes the project in an afternoon.

I shipped Jianghu V3 knowing it wasn’t perfect. The final playtest found nine bugs. Integration between subsystems still had gaps. That’s fine. That’s the draft.

The methodology matters more than the artifact. I built a system where upgrading models is a casting decision, not an architectural one. When the next generation drops, I won’t rebuild my workflow. I’ll redirect the scene with a stronger cast.

The bottleneck for builders has shifted permanently. It’s no longer “can I build this?” It’s “should I build this, and for whom?” That’s a taste question. And taste is the one thing you can’t swap in.

Leon is an AI systems architect and creative technologist based in San Francisco, bridging the Chinese and US AI ecosystems. Find him on LinkedIn and Twitter/X.